How NOT to solve FlareOn Level 6 with symbolic execution

Level 6 of FlareOn 2018 was a challenge involving having to solve 666 similar crackmes. After looking a bit at the problem, I realized it would be a fun challenge to actually solve with symbolic execution using angr and a bit of Binary Ninja. By “fun”, I mean waiting 28 hours to actually receive the flag.

NOTE: This solution is NOT the optimal, best, or fastest solution. I wanted to brush off my angr skills and this challenge was an interesting candidate for that skill growth.

- Recon

- Decryption with Binary Ninja

- Angr script

- Debugging Angr

- Understanding the scramble

- Solving all the problems

- Coming back 2 days later

Recon

As per the norm, gaining a high level view of what the problem is doing is a great place to start.

Looking at the main function we see the following for loop. (Few variables renamed for clarity)

for ( j = 0; j < 666; ++j )

{

printf("Challenge %d/%d. Enter key: ", j + 1, 666LL);

if ( !fgets(input_buff, 0x80, stdin) )

return 0xFFFFFFFFLL;

input_len = strlen(input_buff);

sub_402DCF((__int64)input_buff, input_len, (__int64)&counter);

for ( k = 0; k < strlen(input_buff); ++k )

*((_BYTE *)&key_buff + k) ^= input_buff[k];

sub_4037BF((__int64)*argv);

}

The basics of the challenge can be seen in this function:

- Input is

0x80characters fromstdin - Buffer is passed to

sub_402DCFalong with its length - That buffer (might be modified) is then

xor‘ed with anotherkey_buffbuffer argv[0]is then passed tosub_4037BF

The gist of the sub_402DCF function is below. (Variables have been renamed as well).

__int64 __fastcall sub_402DCF(__int64 input_buff, unsigned __int64 a2, __int64 counter)

{

for ( i = 0; ; ++i )

{

result = i;

if ( i >= 33uLL )

break;

...

xor_bytes(

*(&stru_605100.function_addr + 0x24 * i), ; xor_buff1

*(&stru_605100.function_length + 0x48 * i), ; xor_length

*(&stru_605100.xor_key + 0x24 * i) ; xor_buff2

);

if ( !(*&stru_605100.function_addr + 0x24 * i)(

*(&stru_605100.input_offset + 0x48 * i) + input_buff,

*(&stru_605100.input_length + 0x48 * i),

&stru_605100.data + 0x48 * i)

)

{

...

exit_and_die();

}

xor_bytes(

*(&stru_605100.function_addr + 0x24 * i), ; xor_buff1

*(&stru_605100.function_length + 0x48 * i), ; xor_length

*(&stru_605100.xor_key + 0x24 * i) ; xor_buff2

);

...

}

}

In English:

- Decrypt some function whose address is found in a global struct

- Call the decrypted function with some piece of the input string

- If the result is zero, kill the process

- Continue this loop 33 times

The global data at 0x605100 was structured as the following in IDA:

00000000 decode_struct struc ; (sizeof=0x2C, mappedto_6)

00000000 function_addr dq ?

00000008 function_length dd ?

0000000C input_offset dd ?

00000010 input_length dq ?

00000018 xor_key dq ?

00000020 data dd ?

0000002C decode_struct ends

The key portions here is that each function is only working on a small subset of the full input string. The slice that each function is working on could be listed as input_string[input_offset:input_offset+input_length].

Let’s take a look at one of these decrypted function.

signed __int64 __fastcall sub_40111E(__int64 input_buff, unsigned int input_length, __int64 solution_buff)

{

unsigned int i; // [rsp+24h] [rbp-4h]

for ( i = 0; i < input_length; ++i )

{

if ( *(_BYTE *)(i + solution_buff) )

{

if ( *(_BYTE *)(i + input_buff) != *(_BYTE *)(i + solution_buff) )

return 0LL;

}

else

{

*(_BYTE *)(solution_buff + i) = *(_BYTE *)(i + input_buff);

}

}

return 1LL;

}

This function is a simple memcmp that returns 1 when successful. (To be honest, this is the only function that I actually looked at, so I have no idea what the other functions actually did)

With this knowledge, we can attempt to use Angr to solve each of these functions for a result of 1.

Decryption with Binary Ninja

We don’t want to use Angr to execute everything entirely, we only want to use Angr to solve an input to each function such that it results in 1. To do this, we could decrypt all the functions ourselves since we know the decryption method. Any efforts we can offload from Angr results in somewhat faster results (at least in theory).

Again, having the steps necessary to accomplish this task helps guide the process.

- Extract all of the global structs

- Decrypt the current binary

- Solve each of the functions found in the global structs for a return value of

1

To accomplish the first two steps, we can use a quick Binary Ninja script.

"""

reconstruct.py

"""

from binaryninja import *

from collections import namedtuple

import sys

Struct = namedtuple('Struct', ['function_addr', 'offset', 'length'])

def decrypt(filename):

bv = BinaryViewType.get_view_of_file(filename)

# Known global addresses

code_addr = 0x605100

len_addr = 0x605108

key_addr = 0x605118

data = []

for x in range(33):

# Extract each of the values

curr_len = struct.unpack('<I', bv.read(len_addr, 4))[0]

curr_code = struct.unpack('<I', bv.read(code_addr, 4))[0]

curr_key = struct.unpack('<I', bv.read(key_addr, 4))[0]

# Save the current data to be used in our Angr script

curr_struct = [x for x in struct.unpack('<QIII', bv.read(code_addr, 4 * 5))]

data.append(Struct(curr_struct[0], curr_struct[2], curr_struct[3]))

# Perform the xor operation and save it to the current project

cipher_code = bv.read(curr_code, curr_len)

xor_key = bv.read(curr_key, curr_len)

for i, (code, key) in enumerate(zip(cipher_code, xor_key)):

curr_char = chr(ord(code) ^ ord(key))

bv.write(curr_code + i, curr_char)

code_addr += 288

len_addr += 288

key_addr += 288

# Save the modifications to a new binary

bv.save('./magic_patched')

return data

The script reads the decrypted function as well as the xor key using the global structure data. It then performs the xor operation and saves the decrypted function in a new file called magic_patched. The resulting global struct data is also returned back to the Angr script when this decrypt function is called. That data looks something like the following:

Struct(function_addr=4197442, offset=3, length=1)

Struct(function_addr=4201805, offset=43, length=2)

Struct(function_addr=4198592, offset=18, length=3)

Struct(function_addr=4197901, offset=7, length=3)

Struct(function_addr=4205154, offset=62, length=2)

With this information extracted and saved into a patched binary, we can begin constructing our Angr script to solve each of these functions one at a time.

Angr script

Let’s start with a script that can give us the correct input of the first function.

We start with a few global variables.

result = '?' * 0x45

global_addr = 0x605100

n = 0

Since each function works on a different piece of the input, we start with a giant string of ? and can fill in each piece as we come up to it.

from reconstruct import decrypt

new_filename = './magic'

data = decrypt(new_filename)

We use our previous decrypt function with the current binary to write the decrypted binary to ./magic_patched and return the global Structs with which we can use with Angr.

proj = angr.Project('./magic_patched', load_options={"auto_load_libs": False})

state = proj.factory.blank_state(addr=data[n].function_addr,

add_options={angr.options.LAZY_SOLVES})

Instantiate the Angr project with our newly decrypted binary and create a blank_state at the first decrypted function address. Because we are using a blank_state, we will have to setup the arguments to that state, but that will come later.

input_addr = 0x10000 * n

key_len = data[n].length

input = claripy.BVS("input", 8*(key_len))

for i in xrange(key_len):

state.add_constraints(input.get_byte(i) != 0)

state.memory.store(input_addr, input)

Create a symbolic input buffer using the length value from the global data structure. At first, simply setting a constraint such that the input bytes are not zero. We then store the symbolic input at some random address that will be passed to the decrypted function. With the symbolic input done, now we can setup the function parameters.

key_addr = (0x605120 + n*0x120)

state.regs.rdi = claripy.BVV(input_addr, 8*8)

state.regs.rsi = claripy.BVV(key_len, 8*8)

state.regs.rdx = claripy.BVV(key_addr, 8*8)

state.stack_push(0xdeadbeef)

Using the x64 ABI, we set the first argument to rdi, the second argument to rsi, and the third argument to rdx. Finally, we push a known value (0xdeadbeef) onto the stack. This will act as our return address and can be used in our analysis to know when the function has returned.

Lastly, we create our simulation_manager and can explore based on two yet-to-be-written functions: find_func and avoid_func.

simgr = proj.factory.simulation_manager(state)

simgr.explore(find=find_func, avoid=avoid_func)

We can start with the easy function first: avoid_func. Because we set a known return address to 0xdeadbeef we can use that to stop execution of various paths that are returning to 0xdeadbeef but with a return value (or rax) of 0.

def avoid_func(state):

if state.regs.rip.args[0] == 0xdeadbeef and state.regs.rax.args[0] == 0:

return True

The find_func is a bit more intersting. We want to confirm that we are returning to 0xdeadbeef with a return value of 1. If those are true, we then want to solve for the input value that caused this state. With the correct value in hand, we can place the solved value in our result string of ?.

def find_func(state):

if state.regs.rip.args[0] == 0xdeadbeef and state.regs.rax.args[0] == 1:

global result

ans = state.solver.eval(input, cast_to=str)

offset = data[n].offset

ans_len = data[n].length

result = result[:offset] + ans + result[offset+ans_len:]

print(n, result)

return True

With the script finished for the first function, let’s run it to see if we receive a result.

Start <BV64 0x400c42> - rdi: <BV64 0x0> rsi: <BV64 0x1> rdx: <BV64 0x605120>

e

<SimulationManager with 1 found, 1 avoid>

('RESULT', '???e?????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????')

Fantastic, so we have one function of the first binary solved. Wrapping the entire method block in a for loop to increment the n value can then solve the remaining functions.

Debugging Angr

The next section is a bit of an aside as to one of the huge debugging efforts I needed to do to get this to work. I’m still not exactly sure why this is the case, but wanted to document it in case others run into these problems.

After wrapping the above code in a for loop to increment n, we are returned with a bit of a problematic error messsage from Angr:

Start <BV64 0x401ae8> - rdi: <BV64 0x140000> rsi: <BV64 0x3> rdx: <BV64 0x6067a0>

(20, 'like??? ine Hf???Ah,thi ??????r?????thege ofno?? ??????\x02\x0f\x81 isin??the')

('RESULT', 'like??? ine Hf???Ah,thi ??????r?????thege ofno?? ??????\x02\x0f\x81 isin??the')

Start <BV64 0x40130f> - rdi: <BV64 0x150000> rsi: <BV64 0x2> rdx: <BV64 0x6068c0>

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

angr.errors.SimUnsatError: ('Got an unsat result', <class 'claripy.errors.UnsatError'>, UnsatError('CompositeSolver is already unsat',))

Interesting, an unsat error. This means that Z3, the SAT solver used by angr to evaluate the expressions Angr generates, couldn’t find a valid input to cause the function to return 1. Usually when this happens, a walk through over the code was necessary to ensure no silly mistakes occured. In this case, nothing crazy came out of it, so it is time to start debugging the Angr execution itself.

Let’s start with understanding exactly which n values are causing these errors. We can add a try/except block around the .eval code and only print errors.

def find_func(state):

if state.regs.rip.args[0] == 0xdeadbeef:

if state.regs.rax.args[0] == 1:

global result

try:

ans = state.solver.eval(input, cast_to=str)

except:

print('ERROR: n={}'.format(n))

With this we only see one error case:

ERROR: n=21

We can now remove the for loop and simply isolate the n=21 case for further analysis.

Let’s start with adding two hooks for when memory is read and written to see if anything odd is occuring. Angr gives us the ability to execute code before or after various trigger points in simulation. Check out their docs for further information.

Adding a simple hook for mem_read and mem_write might give us interesting insight into how the memory is being used currently.

def hook_mem_write(state):

if not state.inspect.instruction:

return

print('{:x} [{}] = {}'.format(state.inspect.instruction,

state.inspect.mem_write_address,

state.inspect.mem_write_expr))

def hook_mem_read(state):

if not state.inspect.instruction:

return

print('{:x} {} = [{}]'.format(state.inspect.instruction,

state.inspect.mem_read_expr,

state.inspect.mem_read_address))

The hooks are documenting the address being written to/read from and the expression being written to/read from. We now can add these hooks immediately after we create our blank_state object.

state = proj.factory.blank_state(addr=data[n].function_addr,

add_options={angr.options.LAZY_SOLVES})

state.inspect.b('mem_write', when=angr.BP_AFTER, action=hook_mem_write)

state.inspect.b('mem_read', when=angr.BP_AFTER, action=hook_mem_read)

Executing this, we come across something a bit pecular.

401398 [<BV64 0x7fffffffffeffec>] = <BV32 0x0>

401461 <BV32 0x0> = [<BV64 0x7fffffffffeffec>]

4013a4 <BV8 mem_7fffffffffeffeb_2_8{UNINITIALIZED}> = [<BV64 0x7fffffffffeffeb>]

4013a8 <BV32 0x0> = [<BV64 0x7fffffffffeffec>]

4013ab <BV8 0> = [<BV64 0x7fffffffffefee0>]

We are reading some uninitialized value at address 0x4013a4. Hmm, I wonder if Angr can be told to set uninitialized memory to zero for instance as an option somewhere. Turns out, there is an option in angr to zero out unconstrained memory. This was found by a bit of reading into the options found in their documentation

`ZERO_FILL_UNCONSTRAINED_MEMORY`

Make the value of memory read from an uninitialized address zero instead of an unconstrained symbol

Let’s add this option and see if this fixes the evaluation.

state = proj.factory.blank_state(addr=data[n].function_addr,

add_options={angr.options.LAZY_SOLVES,

angr.options.ZERO_FILL_UNCONSTRAINED_MEMORY})

Lo’ and behold, we are presented with the key to the first level.

WARNING | 2018-09-18 18:02:56,708 | angr.analyses.disassembly_utils | Your verison of capstone does not support MIPS instruction groups.

<BinaryView: './magic', start 0x400000, len 0x217640>

Start <BV64 0x400c42> - rdi: <BV64 0x0> rsi: <BV64 0x1> rdx: <BV64 0x605120>

e

(0, "'e'")

(0, '???e?????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????????')

Start <BV64 0x401d4d> - rdi: <BV64 0x10000> rsi: <BV64 0x2> rdx: <BV64 0x605240>

of

(1, "'of'")

(1, '???e???????????????????????????????????????of????????????????????????')

Start <BV64 0x4010c0> - rdi: <BV64 0x20000> rsi: <BV64 0x3> rdx: <BV64 0x605360>

...

tart <BV64 0x40100d> - rdi: <BV64 0x1e0000> rsi: <BV64 0x3> rdx: <BV64 0x6072e0>

ace

(30, "'ace'")

(30, 'likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll ?inr???owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe')

Start <BV64 0x401689> - rdi: <BV64 0x1f0000> rsi: <BV64 0x1> rdx: <BV64 0x607400>

.

(31, "'.'")

(31, 'likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll .inr???owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe')

Start <BV64 0x40185a> - rdi: <BV64 0x200000> rsi: <BV64 0x3> rdx: <BV64 0x607520>

ds

(32, "'ds '")

(32, 'likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll .inrds owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe')

Understanding the scramble

Testing this solution, we are presented with the second challenge prompt.

(ins)$ /tmp/magic

Welcome to the ever changing magic mushroom!

666 trials lie ahead of you!

Challenge 1/666. Enter key: likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll .inrds owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe

Challenge 2/666. Enter key:

Testing the solution a second time, we see something a bit weird:

(ins)$ ./magic

Welcome to the ever changing magic mushroom!

666 trials lie ahead of you!

Challenge 1/666. Enter key: likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll .inrds owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe

Challenge 2/666. Enter key:

No soup for you!

root at e23798e6021f in /tmp

(ins)$ ./magic

Welcome to the ever changing magic mushroom!

666 trials lie ahead of you!

Challenge 1/666. Enter key: likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll .inrds owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe

No soup for you!

The first time, it works, but the second and subsequent time, it fails. Turns out, the binary is changing out from under us. Looking at the SHA-1 of the original binary to this new binary confirms this suspicion.

(ins)$ sha1sum /tmp/magic ./magic

56017fcf56b3d14979fffc6701b3c31a896263d2 /tmp/magic

4267990d820b5ba0940cd01df6d7a97d254de091 ./magic

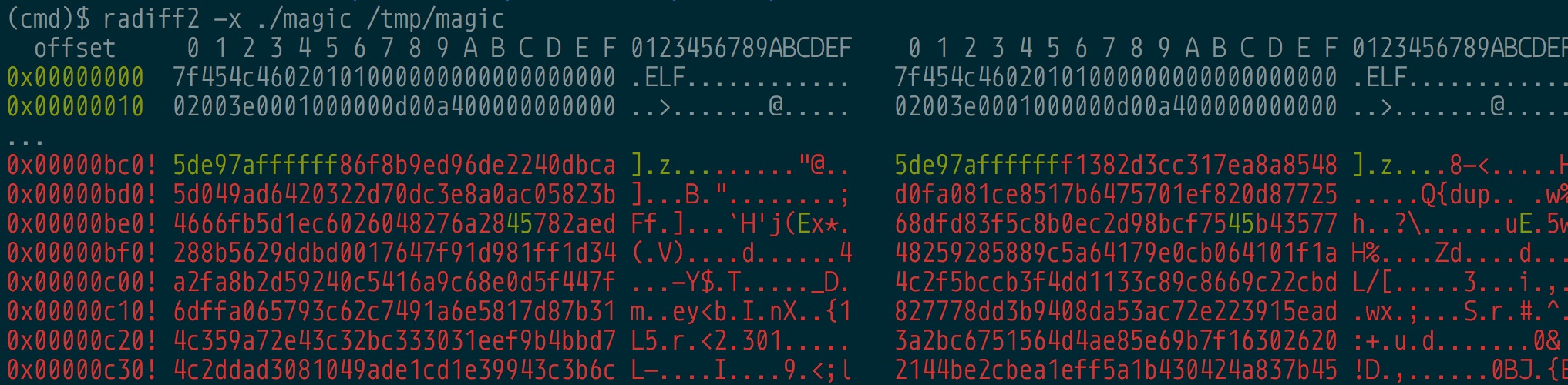

Let’s take a look at the diff of the binaries to see if anything pops out at us. radiff2 from radare2 really helps visualize this.

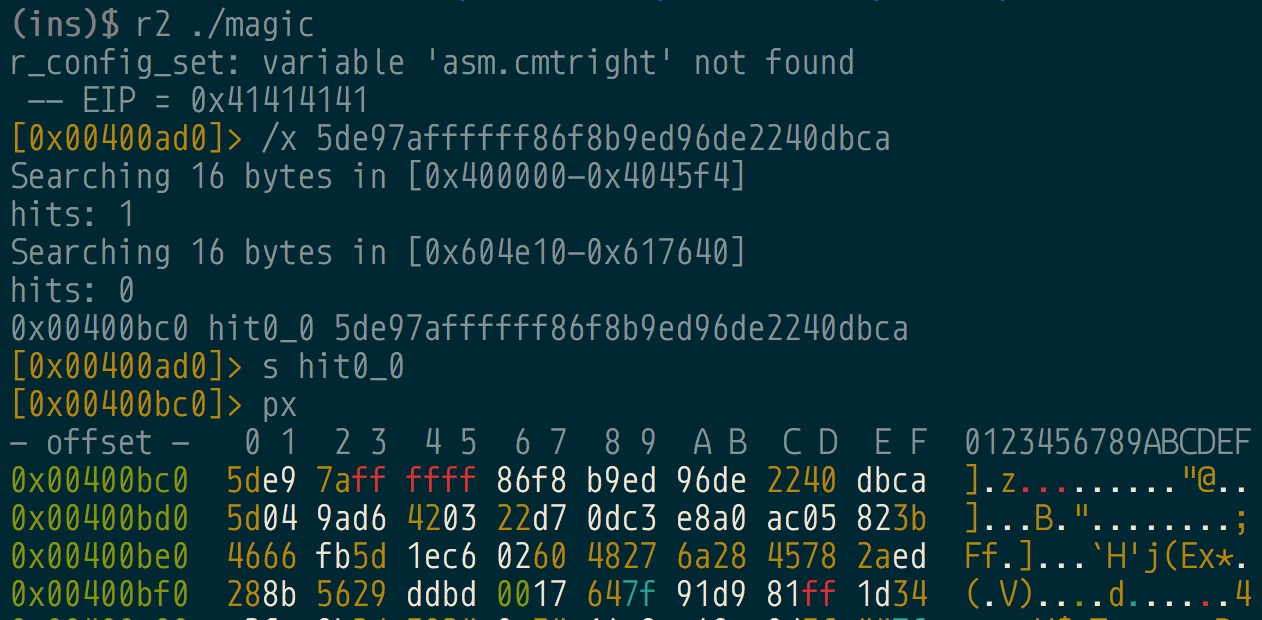

radiff2 gives us the offset in the file on disk rather than the virtual address. Let’s find these locations using radare2. Let’s start with looking at the first picture’s diff in the original magic file.

Ah interesting, the diff starts at address 0x400bc6. Looking back at our global data from the Binary Ninja script, we see that 0x400bc6 is actually one of the functions called.

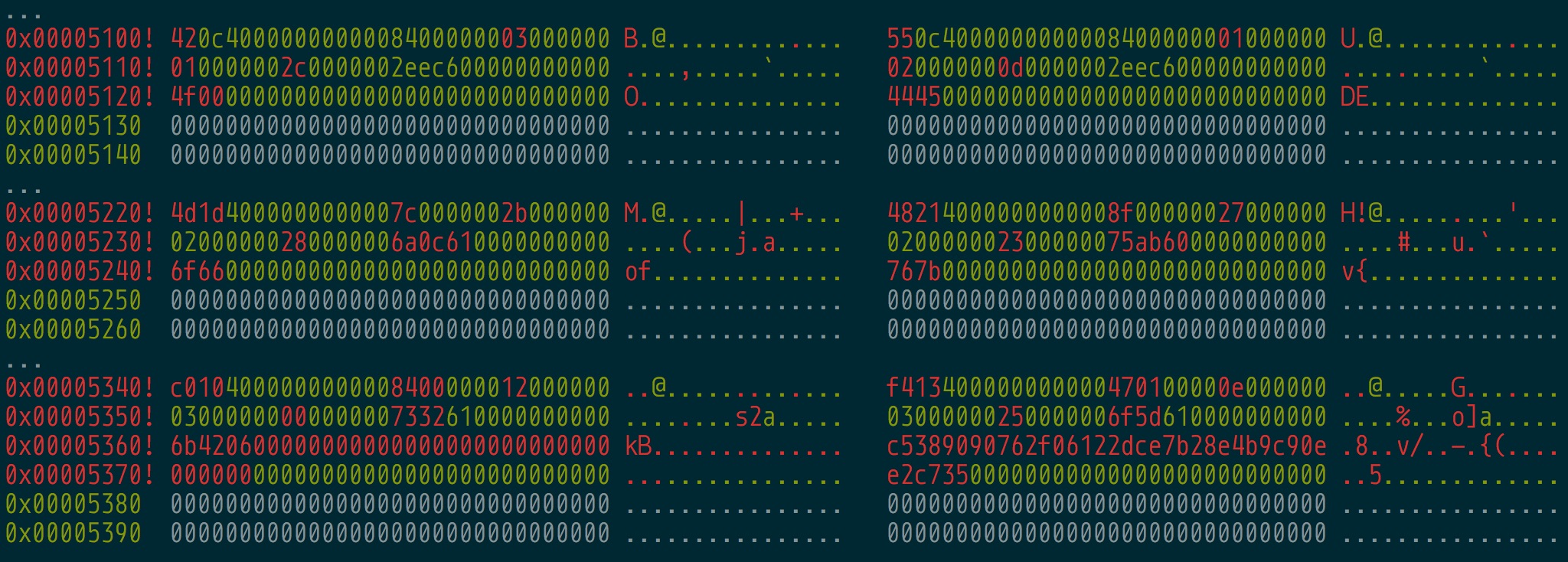

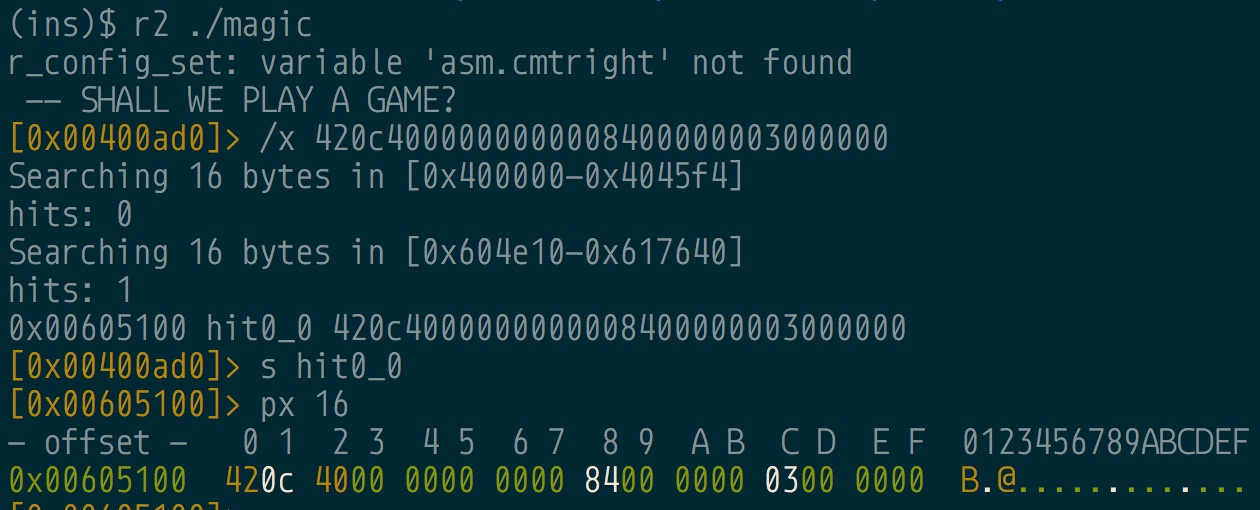

Let’s also look at the second picture’s diff as well.

Fascinating, so the diff is at 0x605100, the global address containing the list of structs in memory where the encrypted functions are located.

So each time we enter a correct key, the binary writes a new “scrambled” binary to disk that mixes around the various functions and the keys used to encrypt these functions.

Small aside, I didn’t reverse the “scramble” function at

sub_4037BF. I’m only assuming these things based on the diffs of the binaries. If we really wanted to solve this properly, we’d reverse this function to understand how the scramble happens. Due to the fact that earlier in binary a static key is passed tosrand, we can know the random values used for this scrambling.

Knowing that we can solve one binary and that each time the binary is executed with correct keys, a new binary is written, we can script this process to extract each binary, one at a time, to eventually solve the entire puzzle.

Solving all the problems

With our current knowledge, the steps to progress to the final solution could be the following:

- Execute the original

magicproblem using all the keys we have currently solved - Input invalid key to force exit the challenge

- Solve the newly written scrambled binary using our existing Angr script

- Add the newly found key to the list of keys

We simply have a few pipelining problems to solve the remainig 665 binaries.

Using pwntools, we execute the original binary and send all the keys we currently have to the binary to morph the binary to the current state. We can then kill the process and copy off the current binary to then solve with our Angr script.

keys = [

'likehot ine HfaceAh,thi ll .inrds owthege ofno w bl yong isinurthe',

]

shutil.copy('./magic_original', './magictemp')

os.chmod('./magictemp', 0o777)

proc = process('./magictemp')

for k in keys:

proc.sendline(k)

# Force binary to die

proc.sendline()

proc.kill()

# Copy off the newly morphed file into its own binary

new_filename = './magic{}'.format(str(iteration).zfill(3))

shutil.copy('./magictemp', new_filename)

With the newly morphed binary in hand, we can use that binary with our Angr script to find its key.

# Copy off the newly morphed file into its own binary

new_filename = './magic{}'.format(str(iteration).zfill(3))

shutil.copy('./magictemp', new_filename)

for n in xrange(33):

proj = angr.Project(new_filename, load_options={"auto_load_libs": False})

...

print('RESULT', result)

keys.append(result)

Once we find the new key, we append it to the list of existing keys, and continue this process for 666 times.

Coming back 2 days later

This process was all fine and good, except each iteration took roughly 2.5 minutes per cycle. This was fine in the first case, but over 666 times, we end up with almost 28 hours of computation to find the finished result.

>>> 2.5 * 666 / 60

27.75

Nevertheless, waiting patiently resulted in the final key.

Welcome to the ever changing magic mushroom!

666 trials lie ahead of you!

Enter key: Challenge 1/666.

Enter key: Challenge 2/666.

...

Enter key: Challenge 665/666.

Enter key: Challenge 666/666.

Enter key: Congrats! Here is your price:

mag!iC_mUshr00ms_maY_h4ve_g!ven_uS_Santa_ClaUs@flare-on.com

Even though this solution was quite lengthy and time consuming, the knowledge gained from small pieces of Angr like how to leverage the inspect hooks, was well worth the fun and effort.

git clone https://github.com/ctfhacker/ctf-writeups